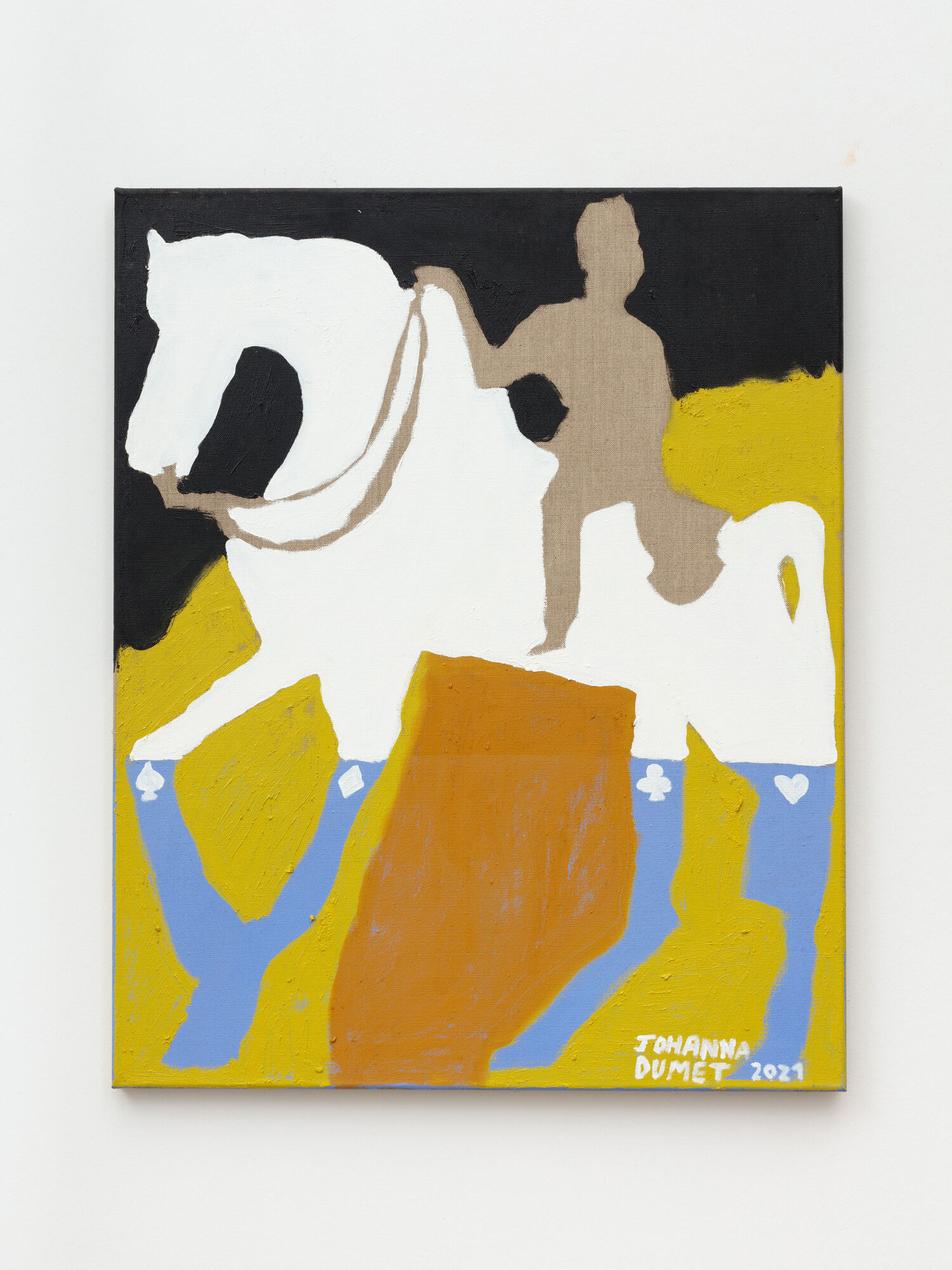

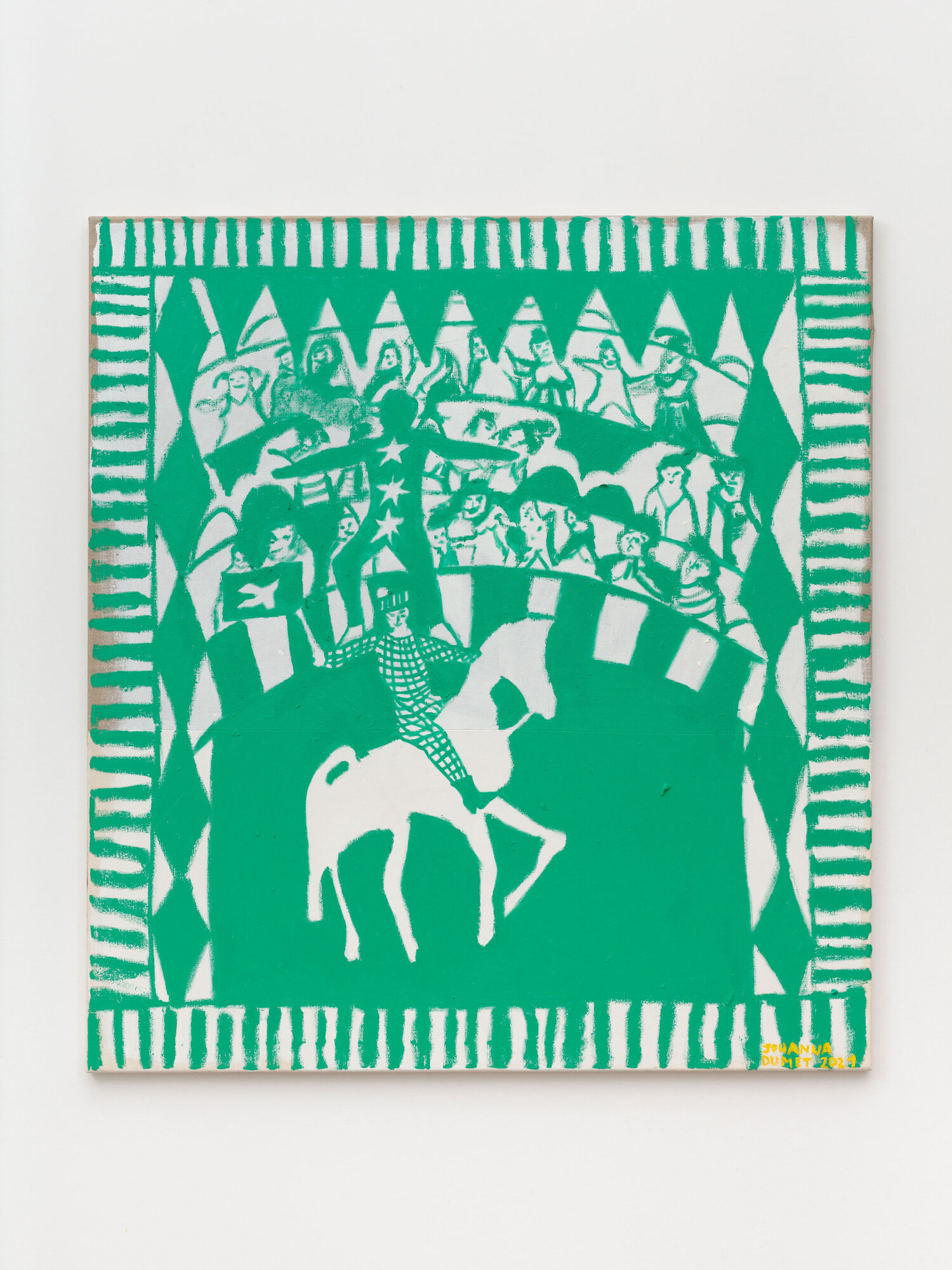

Johanna Dumet 'Geil again'

JOHANNA DUMET

'Geil again'

September 4 – 24, 2021

OPENING: Saturday, September 4, 2021, 12 - 6 pm

Opening Times:

Wednesday - Friday, 3 – 6 pm

Book your visit – here. For the exhibition opening on Saturday you will not need a time slot.

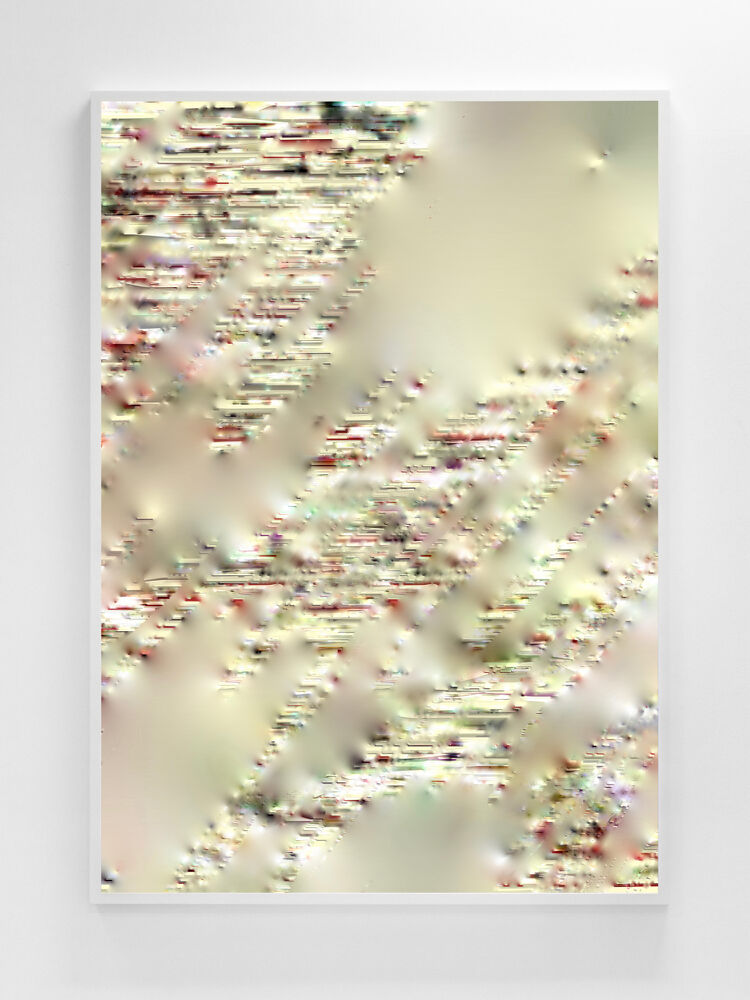

Eine der Definitionen, die man zu “Nichts” finden kann, ist: “Etwas Abwesendes, dessen Anwesenheit erwartet wurde”. So ähnlich funktionieren die Arbeiten der neuen Serie von Johanna Dumet. Die Malerin, geboren 1991 in Frankreich, hat sich zuvor mit großen, opulent gedeckten Tischszenerien einen Namen gemacht. Dort gab es alles im Überfluss: Schalentiere, Alkohol und Designerhandtaschen.

Nach diesem Überfluss und epochalem Gelage wendet sie sich nun dem Gegenteil zu. Anstatt etwas zu malen, malt sie jetzt: nichts. Oder eben das, was sich ergibt, wenn man alles andere malt, nur eben nicht das, worum es eigentlich geht. Das hat den Effekt, dass das Nicht-Ausgesprochene, das Nicht-Gesagte umso klarer hervortritt.

Und so malt Dumet eben alles, nur keine Pferde oder Kamele. Beide sind unabdingbare Begleiter*innen der Kulturentwicklung in ihren jeweiligen Lebensräumen gewesen.

Dabei ist das Pferd innerhalb des Europas nicht nur als Nutztier wichtig, sondern auch als Prestige- und Kunstobjekt. Ähnlich verhält es sich in Wüstenregionen mit Kamelen.

Sie konzentriert sich auf Farben, die sie so aneinander setzt, dass daraus die Flächen entstehen, die das Pferd oder Kamel dann im Negativbild entstehen lassen.

Das Pferd ist wohl eines der am häufigsten gemalten Tiere. Schon vor 20.000 Jahren haben ihre Bewohner*innen die Höhle von Lascaux unter anderem mit Pferden vollgekritzelt und die Pferdeskulpturen, die man auf dem Markusdom in Venedig sehen kann, sind auf das 3. Jahrhundert datiert. Doch meistens geht es nicht um das Pferd an sich, sondern um den Status, den das Pferd demjenigen verleiht, der auf ihm drauf sitzt. Jeder Feldherr hat sich irgendwann in voller Montur auf seinem Streitross abbilden lassen. Dazu erfährt man immer wer derjenige ist, der da so stolz und siegessicher hoch zu Ross sitzt, aber nie etwas über das Pferd. Pferde sind die wohl wichtigsten und am häufigsten übersehenen Nebendarsteller der Geschichte.

In der Romantik gab es eine kurze Phase, in der Pferde allein dargestellt wurden. Eugène Delacroix malte, nach einem Besuch in Marokko fast manisch Pferde. Theodore Géricault war leidenschaftlicher Reiter und widmete ihnen und ihrer Anmut und Kraft mehrerer Serien. Ebenso Edgar Degas, der sich besonders für die Bewegungsabläufe des Pferdes interessierte.

Doch das Pferd ist nicht nur ein Sujet der Malerei oder der Bildhauerei. Man kann sagen, dass es unsere Gesellschaft, wie sie heute ist, ohne das Pferd nicht geben würde. Erst durch die Zähmung von Pferden begannen die großen Völkerwanderungen, konnte man Transportwege erschließen und auch für die Kriegsführung waren Pferde – entgegen ihrer Natur als Fluchttiere – unersetzlich. Ein großer Teil der beginnenden Industrialisierung wurde durch den Einsatz von Pferden ermöglicht. Und neben all diesen Verdiensten sind sie auch immer Prestigeobjekte, ähnlich dem, was heute die “dicken Karre” ist gewesen. Erst jüngst ist eine Debatte um das Pferd “Saint Boy” entbrannt, der den Sieg einer olympischen Fünfkämpferin vereitelt hat. Die Bilder davon, wie das Pferd mit gebleckten Zähnen die Augen in Panik verdreht, von seiner Reiterin weiter angetrieben wird, während sich ihr eigenes Gesicht wegen des drohenden Verlusts der Medaille weinend zur Fratze verzieht, gingen um die Welt. Diese Bilder haben eine neue Debatte um das Pferd als Sportgerät entfacht. Denn obwohl das Pferd kaum noch als Nutztier gebraucht wird, sondern Reiten eine privilegierte Freizeitaktivität ist, wird es im Reitsport oftmals noch als Sportgerät betrachtet. Man sieht meistens den Menschen auf dem Pferd, nicht das Pferd.

Ganz ähnlich verhält es sich mit dem Kamel, das nicht nur in seiner Funktion als Lastentier für den Menschen unabdingbar ist. Es ist gleichzeitig Woll- und Milchlieferant, der Kot wurde als Brennmaterial verwendet. Ohne ein Kamel hätte man ein Problem. Oder zumindest ein nicht unwesentlich härteres Leben. Dafür bekommen diese Tiere als eigenständige Akteure erstaunlich wenig Aufmerksamkeit und definieren sich ausschließlich über die Bedeutung, die ihnen vom Reitenden zugeschrieben wird.

Genau das leuchtet Dumet mit ihren Negativbildern gezielt aus. Die Bilder bezeichnet sie als “nackt”. Sie versuchen nichts zu verschleiern, sie tragen kein Make-Up und keinen Schmuck. Sie schmücken nichts aus, sondern konzentrieren sich auf das, was wirklich nötig ist, um die Geschichte zu erzählen. Als sie begonnen hat, Pferde zu malen, ist sie mit aufgespannten Leinwänden, ihren Farben und einem Buch über Staffordshire-Porzellan-Figurinen nach Dänemark gefahren, um sich dem neuen Werkkomplex in Ruhe widmen zu können.

Die Staffordshire-Porzellan-Figuren, von denen man viele – vor allem die apart treudoof glotzenden Hunde – auch in ihren anderen Serien finden kann, stammen aus dem 19. Jahrhundert. Viele von ihnen sehen aus, als wären sie von Menschen bemalt worden, die noch nie zuvor einen Hund oder ein Pferd gesehen haben, was diesen Pferden und Hunden ein etwas abstrakt-zerrüttetes Aussehen gibt. Sie sehen aus als wäre ihre vorherige Nacht etwas zu lang gewesen und sie eigentlich erstmal einen starken Kaffee trinken müssten.

Diese verzerrten Darstellungen funktionierten also als Vorlagen für Dumets Bilder. Sie hat sich nicht an einer naturgetreuen Darstellung orientiert, sondern vielmehr an der Vorstellung, dem gesellschaftlich verankerten Bild eines Pferdes. Gerade deswegen ist die Entscheidung, alles zu malen, nur das Pferd nicht, so konsequent.

Und in dieser Konsequenz setzt sie dem Pferd und dem Kamel ein viel eindringlicheres Denkmal, indem sie darauf verzichtet, an dem brutalen Prozess der Bildaneignung teilzunehmen.

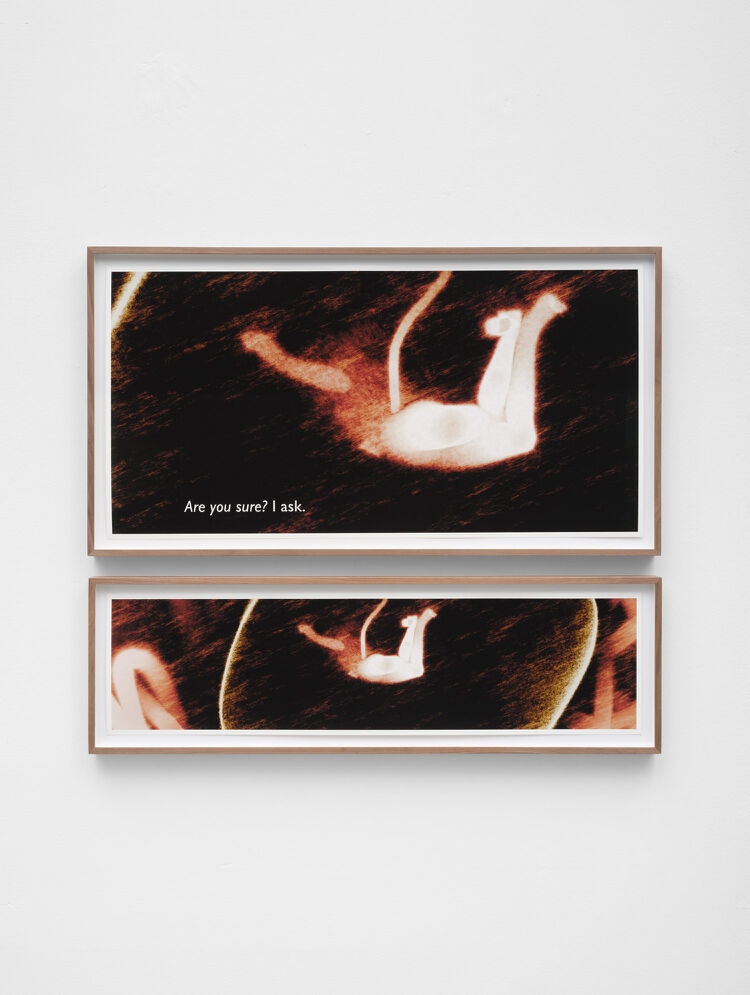

Der Schwere des Themas wiederum stehen die Titel, die meistens popkulturelle Referenzen sind, gegenüber. Sie geben den Bildern das, was Dumet “Lightness” nennt. Etwas, da in ihrem Fall mehr als lediglich Leichtigkeit meint. Es meint auch Zugänglichkeit, Wärme und etwas Einladendes. Denn über Anspielungen an Sex and the City oder klassische Western spannt sie den Bogen von Napoleon, der auf einem Pferd sitzt, zu Carrie Bradshaw, die auf einem Kamel durch die Wüste gondelt. Gemeinsam ist ihnen: Derjenige, der oben sitzt, hat immer einen Namen. Und so erschafft Dumet über die Auslassung und das Nichtmalen genau das Gegenteil von nichts.

Text – Laura Helena Wurth

The exhibition is part of the exhibition series 'Hannah Sophie Dunkelberg, Johanna Dumet, Lena Marie Emrich', which we will be showing from 13 August to 29 October.

Kindly supported by Stiftung Kunstfond and Neustartkultur.

One of the definitions that can be found of “nothing” is: “something absent that was expected to be present.” The works in Johanna Dumet’s new series function in a similar manner. The painter, born in France in 1991, had previously made a name for herself with large-scale, opulently filled scenes of tables. Everything occurred in them in abundance: shellfish, alcohol, and designer handbags.

In the wake of such abundance and epochal banquets, she is now turning to the opposite. Instead of painting something, she now paints: nothing. Or what transpires when you paint everything else, but not what the work’s actually about. This has the effect of enabling what’s not being articulated, what’s not being said, to emerge all the more clearly. This means Dumet paints everything, except the horses or camels. The two have both been indispensable companions in the cultural development of their respective habitats. Within Europe, the horse enjoys importance not only as a farm animal, but also as an object of prestige, as well as being the subject of art. A similar situation pertains to camels in desert regions.

The artist focuses on colors, which she places adjacently in such a manner that surfaces emerge from them, the horse or camel occurring as negative space. The horse is arguably one of the animals that have been most frequently painted. 20,000 years ago, the inhabitants of the Lascaux cave were already scribbling horses, among other imagery, everywhere, and the horse sculptures to be seen on St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice can be dated to the 3rd century. But most of the time the issue isn’t the horse itself, but the status that the horse confers on whoever is sitting on it. At some point every general had himself depicted in full uniform astride his war horse. Additional information is always provided about who it is sitting on horseback, so proud and confident of victory, but never anything about the horse. Horses are arguably the most important and most overlooked supporting actors in history.

There was a brief time during the Romantic period when horses were depicted alone. After a sojourn in Morocco, Eugène Delacroix began painting horses almost manically. Theodore Géricault was a passionate rider and devoted several series to the animal and its grace and strength, as did Edgar Degas, who was particularly interested in the movements of the horse.

But the horse is not just a motif in painting or sculpture. It could be argued that society today would not exist in its present form without the horse. The great migrations of peoples only began after horses had been domesticated, transport routes could be opened up, and horses were irreplaceable in warfare – contrary to the escape response inherent to their nature. Much of fledgling industrialization was made possible by the use of horses. And in addition to all these merits, they have always also remained objects of prestige, similar to what the “slick limo” symbolizes today. Only recently a debate erupted concerning “Saint Boy, ” a horse deemed responsible for thwarting the victory of an Olympic pentathlete. Images of the horse with bared teeth, rolling its eyes in panic, while being driven on by its rider, her own face becoming a weeping grimace as the impending loss of the medal loomed, was transmitted around the world. The images have sparked a new debate concerning the horse as just a piece of sports equipment. While the horse is rarely used as a farm animal anymore, but riding remains a privileged leisure activity, it is frequently still regarded as merely a piece of sports equipment in equestrian sports. The majority of the time it is the person on the horse that is seen rather than the horse itself. It’s very much a similar case for the camel, which has become indispensable for humanity, and not merely as a pack animal, but also a source of wool and milk, while its manure was traditionally used as fuel. Without the camel we would have a problem, or at least a significantly harder life. In view of the above, these animals receive surprisingly little attention as autonomous protagonists, being exclusively defined instead by the significance assigned to them by their rider.

This is exactly what Dumet highlights in her use of negative space. She describes the paintings as being “naked.” They don’t attempt to conceal anything, they aren’t adorned with make-up or jewelry. They don’t embellish anything, but solely focus on what's really necessary in telling the story. Shortly after she started painting horses, she travelled to Denmark with stretched canvases, her paints, and a book about Staffordshire porcelain figurines, so that she could devote herself to the new group of works in peace.

The Staffordshire porcelain figurines, many of which – especially the dogs with their cute, naively trusting gaze – can also be found in her other series, date from the 19th century. Many of them look as if they had been painted by people who’d never seen a dog or horse before, endowing the horses and dogs with a somewhat abstract, dysfunctional appearance. They look as if the previous night had been a little too long and they were now in real need of a strong coffee.

It is these contorted representations that function as sources for Dumet’s paintings. They’re not based on any lifelike representation, but rather on notions of a socially anchored image of a horse. It’s exactly because of this, that the decision to paint everything except the horse, is so powerful. The result is that in refraining from participating in the brutal process of appropriating an image she’s able to create a much more haunting monument to both horse and camel.

The seriousness of the subject matter is in contrast to the titles, whose primary reference is pop culture. They provide the paintings with what Dumet calls “lightness.” Something which, in her case, means more than just facileness. It also signifies an accessibility, warmth, and something inviting. The allusions to Sex and the City and classic Westerns enable her to span an arc from Napoleon, who sits astride a horse, to Carrie Bradshaw, who ambles through the desert on a camel. What they both have in common is that the person sitting on top always possesses a name. By employing omission and not painting, Dumet is subsequently able to create the exact opposite of nothing.

Text – Laura Helena Wurth